Challenge 1: Linknames, or why I’m giving the domain KingCharl.es to King Charles for Christmas

I’ve given myself 12 Challenges to make the internet a bit better. Here, I explain The Plan for Challenge 1.

I’ve always been obsessed with names. I’ve never been able to properly kick off a creative project until a gut feeling that I’ve got the name right.

I’ve spent hours, days, nights lying awake thinking of names for startups, apps, publications, bands. Their names are a record of how I’ve spent my creative life: Underground Magazine, Go Away, Nudge, Sunday Stories, Shufflepad, Record Supply, Sotion, Cloakist, Radiating, and now 12 Challenges.

Because of my fondness for devising names, I’ve always wondered how they could pull their weight a little more. Could a name act as a kind of signpost, suggesting a specific action to the reader?

It’s not a crazy question, since many names already act in this way. Consider handles. The ‘@’ at the start suggests to the reader that there is an Instagram, TikTok or X account behind the name, and that they are just a couple of taps away from following (often with a helpful icon to suggest which platform to head to).

Likewise hashtags — adding a ‘#’ denotes an online trend that the reader might want to follow, whether on Instagram, TikTok or X.

Both of these are naming conventions, and they’re so widespread that people instantly know which kinds of things they can do when they see them.

My first challenge

My first challenge is to pitch a new naming convention to the world. I’m calling it a linkname, and it can make the internet a bit better by giving creators more autonomy in a world where they are at the mercy of big platforms like Instagram, X and Spotify.

The linkname is a concept that may seem a little obvious at first. I’ll be trying to convince you that there’s value in explicitly identifying the concept, and that creators will benefit from linknames becoming a recognized naming convention. And yes, I also hope to win King Charles over to the linkname side of life.

Here’s the story of linknames: what they are, why they should exist, why they should be recognized — and my plan to get them out there.

Along the way, I’ll talk about various platforms (Spotify in particular) and the way they put creators in a straitjacket.

Let’s start by talking about enshittification.

Enshittification

Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Spotify offer you a Faustian bargain. You get access to billions of people, but at the cost of never truly owning your audience — and having to put up with the platform slowly screwing you more and more over time as they stop caring about non-paying users. Or as Cory Doctorow puts it, enshittification.

I got enshittified for the first time ten years ago. Some friends and I ran a small satirical publication, Underground Magazine (like The Onion for London). We had 1,000 people following our Facebook page, and we’d regularly get over 100 likes on posts.

Then, practically overnight, Facebook turned off the taps. Our posts started to be shown to only 2-3% of our fans — of people who had explicitly chosen to follow us. Our likes per post plummeted to a handful. Facebook offered to show posts to all our fans if we paid them cold hard cash. How kind!

Lazlo’s Hierarchy of Ownership

You’re at risk of enshittification when you don’t own your audience. Let’s consider my brother Lazlo, who makes amazing dream pop under the name Pink Mario. He has thousands of followers across Instagram and Spotify, which is great. Unfortunately though, having followers on these platforms is precarious — since you fundamentally do not own your audience.

We can analyze Pink Mario’s audience with a tool we’ll dub Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Lazlo’s Hierarchy of (Audience) Ownership:

These two pyramids describe what you need from a platform to be able to call yourself a proper owner of the audience you’ve built on it, from the perspective of 1) Data about your audience and 2) Features for interacting with your audience.

With his 6k Instagram followers, Pink Mario gets:

Data-wise, to see who they all are (Directory, Level 3) and some basic statistics (Level 4)

Features-wise, to DM/post to some audience members, sometimes (Post, Notify or DM, Level 4)

Spamming controls impose hard limits on the number of DMs he can send, and posts reach only a very small portion of his followers, so his effective audience size is in the hundreds of people — varying depending on how well the initial audience responds to his posts.

Not great, but the situation with his 2.7k Spotify followers is much worse:

Data-wise, some basic statistics (Level 4)

Features-wise, leaving aside some minimal cross-promotion features, Lazlo’s not even on the pyramid!

It’s incredible to think that this means musicians on Spotify don’t even know who their followers are — only how many they have. And I’m not talking about the 30k listeners of Lazlo’s music, but the 2.7k people who explicitly used the Spotify ‘Follow’ button to become his followers.

Guaranteed Instability

The real kicker on these platforms, as well as others, is the total lack of Guaranteed Stability for Features over time (Level 3), which means that creators have to put up with:

Frequent changes to the algorithms that decide which content is recommended, which often destroy your effective audience size from one day to the next, and are often impossible to understand and work around.

More screen real estate going to paid content over time. Often these changes (like the ads Facebook offered me ten years ago, or Spotify Marquee) are painted as being an exciting opportunity for creators or businesses to promote their content, when in fact they are a reallocation of users’ attention towards creators who can pay.

Cross-promotion abilities varying according to the platform’s whims. Take, for instance, the various ways that X under Elon Musk has become actively hostile to anyone seeking to link to competitors.

The Guaranteed Instability comes from the simple fact of most platforms being run by big tech companies which make decisions in their own self-interest, not in the interests of creators or users.

It’s not just Instagram and Spotify which are light years from allowing creators to access the top of the pyramid — it’s almost every major platform that exists. That’s because it’s inherently part of being a privately-run for-profit platform that you do not and cannot want creators to be able to take their audiences anywhere else.

This doesn’t make it irrational for someone like Lazlo to focus on Instagram and Spotify.

For many creative paths, you simply have to play the platform’s game, which comes with massive potential upsides such as a post going viral, or a song being featured on an official playlist — either of which could cause your audience to 100x overnight. That’s a lottery most creators need to play.

But some creators — often those who have very well-defined audiences and create content in a niche — have responded to enshittification by going straight to the top of the pyramid.

The new owners

Over the last 6 years, egged on by the enshittification of the major platforms, thousands of creators have migrated to platforms like Substack, Patreon, and Ghost.

These platforms are all slightly different, but at their core, they work by the subscription model: creators build an audience which they fully own and can talk to directly via email, instead of via a platform.

Many creators using the subscription model seek to get some small proportion of their audience to pay them monthly, to try to make a living from a small number of dedicated fans. For these creators, occupying the top of Lazlo’s Hierarchy of Ownership is non-negotiable. They simply must be able to take their entire livelihood elsewhere, and not be at the mercy of Guaranteed Instability.

Which got me thinking: we have naming conventions (handles with @, hashtags with #) that clearly signpost the user towards platforms.

What kind of naming convention would help creators who don’t want to depend on platforms?

Signposting a shopfront

A little while ago I started rooting around for a name to release my own music under.

I knew that I wanted minimal platform dependency — because I broke up with an abusive platform two years ago, but also because building an audience that I owned suited the modest goals I had for my niche experimental pop.

One of the first things I had to figure out was the place online that I wanted potential listeners to interact with first — my online ‘shopfront’, if you will. To have minimal platform dependency, I realized I wanted my shopfront to be a website that I owned, not a page on a platform.

But I also knew that I couldn’t opt out of the platforms entirely. Being a musician who’s not on Spotify and Apple Music is incredibly difficult these days, given the huge numbers of people who exclusively use those platforms to listen.

This made me wonder: how could I bake a signpost to my music’s shopfront directly into the name I chose, so that wherever I used the name, it told people where to go?

Enter domains

The answer was: choose a name to release my music under that was also recognizably a website.

Not just any website, but one that I owned. Whether I used this name on or off platforms, in the virtual world or in the real world, it would always be a signpost to tell people where to go.

Making a name like this added an important constraint: it had to be based on a domain that was available to buy.

Fortunately, the world of domains is brimming with options. We’re living through a domain explosion, where every year the venerable endings of .com and .net are joined by fresher kids on the block.

You can drive your .lamborghini to the .party, eat some .pizza and drink some .vodka once you get there, buy .shoes for your .horse or .jewelry for your .fish, and .stream it all .online in cities from .hamburg to .joburg — among hundreds of other funky domain endings (known as top-level domains, or TLDs).

I loaded up my favourite domain-search tool, Domain.Garden, and over the course of several dangerously obsessive weeks went through 143 different potential artist names across dozens of TLDs. Finally, I settled on:

Radiat.in/g did a few things that I liked:

It used a word I liked the sound and meaning of

It looked a bit weird, matching my style of music

And crucially, it was also a website — a page (/g) at the domain radiat.in, which I own

It was now time to road test this unusual name on Spotify and Apple Music.

This mattered to me a lot, because Spotify in particular is a world-class champion at limiting creators’ ability to talk directly to their audiences.

The Spotify straitjacket

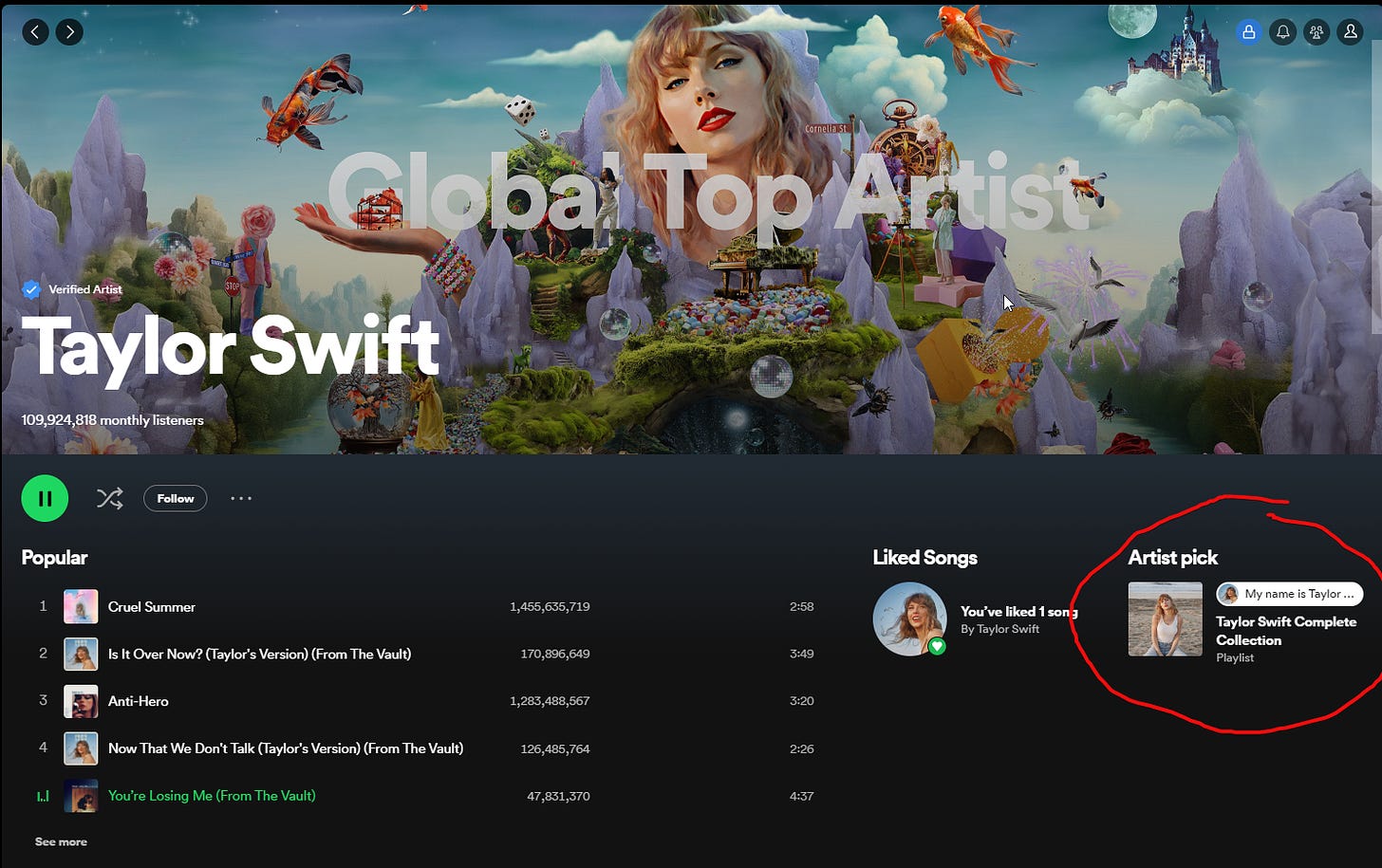

Even if you are a Global Top Artist on Spotify like Taylor Swift, the main control you get over your artist profile — leaving aside the name, profile picture and banner — is something called Artist Pick.

Here it is, tucked away to the side of Taylor’s profile (and by the way, on mobile it only appears once you scroll down):

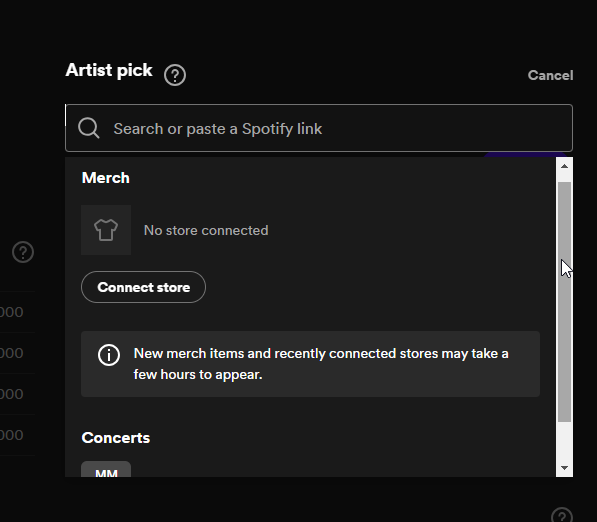

Artist Pick makes it sound like the artist picks what goes there. Not really. Here’s what you can choose from:

You can 1) put in a link to somewhere on Spotify, which is nice for Spotify, 2) sell merch via the official Spotify partner Shopify, using a plugin that boasts a truly impressive 1.1 star rating on their App Store, or 3) add links to your concerts which have to be listed on Spotify’s official ticketing partners.

It’s the most valuable real estate you control on your Spotify profile, right up top, and those are all your choices. Even when you look at Instagram, no particular friend of cross-promotion, the difference is startling: there, you can have up to 5 links of your choice at the top of your profile.

Spotify gives you two other cross-promotion features:

Artist Fundraising Pick (basically a tip jar): a link, shown only on mobile, at the top of your artist profile to a handful of payment providers, so your listeners can send you some money. Spoiler: it probably won’t work.

An ‘About’ section where you can write text describing yourself as an artist. Links you add to the text won’t be clickable — you can add links only to your Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Wikipedia or Soundbetter, and these will appear tucked away to the side of the ‘About’ section. And no, you can’t add a link to your own website.

This all adds up to something we could call the Spotify straitjacket: a set of limitations that are all but impossible to circumvent, which mean creators on the platform are unable to talk to their audiences.

And that’s why I was thrilled when Radiat.in/g was accepted as my artist name:

There, right up top, my name was signposting a place outside of Spotify where I wanted my listeners to come find me.

A nice little Spotify hack, using a new kind of name.

Linknames

I decided to call this kind of name a ‘linkname’.

Linknames are closely related to domain hacks. A classic domain hack is ma.tt, the personal site of Wordpress founder Matt Mullenweg. But linknames are different in two key ways:

Intentionally used as a name, not just a nice domain to direct people to

Optionally can use pages at the domain to form the name, for instance the ‘/g’ in Radiat.in/g

(This second point is important. It makes linknames much easier to create vs. the more limited number of domain hacks.)

I sketched out a definition of a linkname: a name which also is a valid website. Or more precisely:

A noun intentionally used as a name to represent some entity (artist, writer, business etc.)

Contains at least one period (’.’) so that it becomes a valid URL

Optionally contains ‘/’ and any other characters that are valid in a URL

Is a valid URL (if the implied ‘https://’ is added at the start). Easy test — would it work if you typed the linkname into a browser and hit enter?

Then I sat back and wondered whether this was all a waste of time.

What can linknames offer the world?

There are two fairly major catches to linknames:

First, getting people to remember how to spell them correctly. Even my mother struggles to remember how Radiat.in/g is written.

Second, getting people to realize they are signposts to a website. I somehow thought that everyone would recognise a name with a period and then a slash in it to be a signpost to a website. Instead, people think I have a strange fetish for punctuation.

This was particularly problematic since linknames may often be used in contexts where they aren’t clickable — where no handy underline or highlight color reveals them as a link.

But I have never been short of delusional optimism, and am still convinced that linknames have a lot to offer the world. Even if they won’t work for all creators all of the time, they might work for some creators some of the time.

For instance: RandomW.al/k, a street artist who emblazons their name around town in a way that makes it possible for people to find them online and connect with the rest of their art.

Or Cinnamon.Soy/Latte: a specialist coffee truck that’s been stung in its reliance on increasingly expensive Instagram ads, and wants loyal customers to join a newsletter hosted at their site where they’ll get updates on the truck’s location.

Or Wispy.World: a podcast about clouds which proudly lists as a linkname across all podcast platforms to nudge fans towards exclusive content and cloud t-shirts on their site.

None of these exist, but if I put the concept of linknames out there, maybe they would. And if linknames became familiar to enough people, they would signpost to websites in the same way that hashtags signpost to social media.

What I needed to do to, I realized, was pretty straightforward:

Make all of humanity aware of linknames.

The Plan

Once I settled on this well-defined and definitely-achievable goal involving 8.1 billion people, The Plan started coming together thick and fast.

1. Make a linkname manifesto and put it out there

I’m going to write a short manifesto with all the reasons linknames matter, define the concept a little better, give a breakdown of examples that already exist, situations where they can be particularly useful, some FAQs, and post it in various corners of the internet to provoke debate and promote the concept. And yes — it’ll be hosted at linkn.am/es, obviously.

2. Give linknames to celebrities for Christmas

Enter King Charles. I figure that if I’m going to make linknames a thing, I should buy a few and give them to celebrities for Christmas. What better way to establish linknames as a fact on the ground?

Back to my favourite domain tool, Domain.Garden — after a few false starts, I’ve hoovered up KingCharl.es and a couple of others which I’ll keep under wraps for now.

I’m going to write King Charles a letter to give him KingCharl.es for Christmas. I’ll explain what a linkname is, why it’s a Great British Invention and why his acceptance of the gift could do something to make the internet a bit better.

In order for KingCharl.es to be a proper linkname, I’ll need the King to intentionally use KingCharl.es as his new name everywhere. To show him the value of doing this, I’ll pitch the benefits — being able to talk to his followers directly, not having to rely on X or Instagram to deliver His Royal Content to The Royal Audience. I’ll even make a mock up of what the shopfront at KingCharl.es could look like (newsletter subscription, ’Buy me a coffee’ link, purchase Kingly merch, etc.).

I’m not naive. I know there’s a very slight chance that King Charles is not keen to rename himself KingCharl.es in all official channels, so for insurance purposes I’ll also be reaching out to a few other lucky celebrities I find linknames for.

3. Create a linknames generator

If I have time, I’ll try to create a small tool, similar to Domain.Garden, to help people devise new linknames.

4. Write various articles about doing all of the above

What it sounds like.

5. Sit back and watch the linknames roll in

I hope that this activism leads to at least a couple of creators thinking ‘Hmm, I think I’ll use a linkname for my next project’, and that the idea of naming yourself in a way that wrests autonomy back from platforms spreads, slowly but surely.

But my wildest dream is that in ten years time there’ll be at least one widely-recognized, award-winning creator using a linkname.

So there we go — that’s The Plan for Challenge 1, which I’ll be acting on in the next week or so. Make sure to follow here on Substack to find out how it goes, and if you want live updates, you can follow on X here.

Let’s crack on with it!

Thanks to Arjun, Lazlo, Tash and Toby for their support.

linknames is such a memorable term. i think that, as a concept, it has good potential to stick with people who come across it, and hopefully it remains a long-lasting option for creators trying to own their audience. the two caveats you identified are pretty big, though.

remembering linknames is an absolute pain. also, as a consumer, i don't want to go around lots of websites to see what the people i follow do. as tragic as centralization under big platforms like Instagram or Spotify is, there's no denying they're convenient. and, for most people, convenience trumps idealism.

that being said, i respect the shot you took at introducing the term, and i hope the idea sticks. they can probably be quite useful in case someone gets banned (or shadowbanned) from a platform. at least then their followers would know where to find them next. i don't know.

Epic. Roll on, roll on!